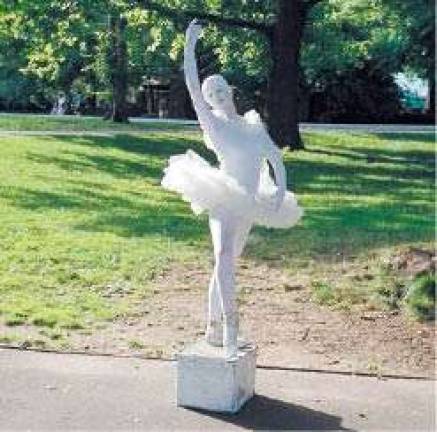

The Central Park Ballerina

How hopes for a career in dance turned into posing for tourists on a box in the park

By Steven Maginnis

Therisa Barber-Shaw came to New York from England hoping to make it big on Broadway. Instead, she's become a hit on a small plastic box in Central Park.

The classically trained dancer performs in the park as a living ballet statue on the box, dancing momentarily when someone drops money in her collection bucket. "You don't always get to plan your life," she explains. "Sometimes you give things a shot, and it sends you in a different direction."

Growing up in Kent, England, Barber-Shaw became interested in dance at age five, when her mother took her to the Royal Ballet in London. She instantly fell in love with the art, and she started taking lessons almost immediately. "There was a point," she says, "where I almost gave up, but my mum knew me better than I knew myself, and she made me stick at it." Barber-Shaw spent two years studying dance at the esteemed London Studio Centre, appeared in a royal gala performance at London's Royalty Theatre, then worked as a dancer and choreographer on cruise ships.

By the year 2000, Barber-Shaw was in New York, but things didn't work out so well. Despite an affiliation with Geoffrey Doig-Marx's Mantis Project Dance Company and a stint as a teacher's assistant at the Broadway Dance Center, she was unable to get sponsorship or broaden her professional experience. After four years as a waitress, she sold calendars for a statue mime performing at Columbus Circle, which bored her. The mime suggested that she use her performing skills by working as a living statue herself. "I said, 'I came here to dance on a big stage, not be a street performer!'" she remembers. "He said, 'It's still art, you'd still be performing.' As much as I fought him, he kept encouraging me. And I saw how much money he was making, and I thought, 'Maybe I can do this.'"

Her work does have drawbacks. Her schedule is contingent on the weather; she has to be ready to work in the park on a moment's notice if the day turns out to be sunny, and she can't make any plans unless she's certain that rain will prevent her from performing on a given day. The conditions of the seasons also affect her. Autumn provides ideally cool, dry weather to perform in, while winter forces her to work in subway stations. Spring produces allergies that cause Barber-Shaw's eyes to run, but the baby powder on her makeup conceals her tearing. Summer humidity causes her pointe shoes to fit imperfectly, and the money comes less easily with more people away.

The abuse from some people is infinitely worse. One time in the subway a man touched the back of her neck, which felt like an electric shock to her after having stood still for so long immersed in her thoughts. Another time in Central Park, a group of children overturned her tip bucket, forcing her to break character and demand that they go elsewhere. The transit police have repeatedly disrupted her act in the subway, though the police in the park have been relatively more supportive. Many people still say rude things to her to get her to break character, but she's become a natural at ignoring them. "You just have to blank them out," she says. "The longer you do it, the easier it gets. Usually these people will get bored and leave. I stick it out longer than they do."

While she continues to pursue dancing, she's also now a certified health coach; she runs Nutritious Harmony, which helps clients maintain their ideal weight, eat better foods, and reduce their cravings, and increase their energy levels to feel better about their well-being. She hasn't turned away from dance, though, and she has also continued to pursuing acting opportunities.

Could all of her efforts as a performer lead to the big career she hoped for when she arrived in America? Barber-Shaw is philosophical about the future. "I live in the moment. Tomorrow hasn't happened, so I'm not going to worry about it. As long as I'm making good money and I'm in good shape, I'll carry on doing my act."