Old Smoke: The Death of Daniel Burros: A Jewish Klansman who did more than just hate himself

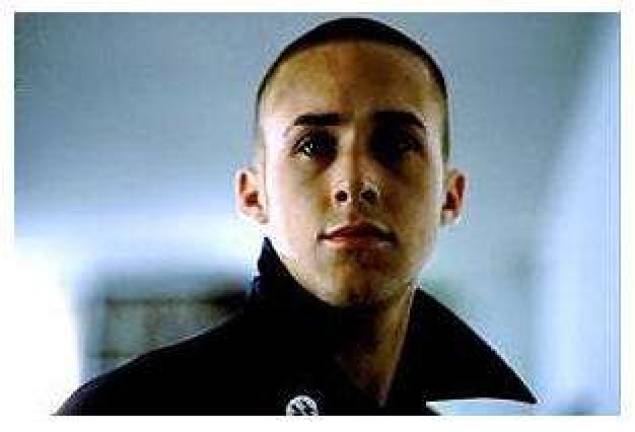

The Times reporter was wrapping up his breakfast interview with the Grand Dragon of New York, the state boss of the Ku Klux Klan. They were in a luncheonette near Lefferts Blvd. in Queens, a little before 9:00 a.m. on Fri., Oct. 29, 1965. They had gone over the Klansman's education, jobs, and military career. Then John McCandlish Phillips asked Daniel Burros how he had become a Nazi. The 28-year-old Burros, squat, blue-eyed, with crew-cut blond hair, talked about his admiration of the Third Reich and his hatred of the Jews, gloating that their purge in the United States would be far more violent than it had been in a "civilized and highly cultured" country like Germany.

The conversation continued until Phillips murmured, "Your parents were married by the Reverend Bernard Kallenberg in a Jewish ceremony in The Bronx."

Before leaving the luncheonette, Burros said that he would kill Phillips.

Daniel Burros, son of George and Esther Sunshine Burros, grandson of Russian Jews, was born March 5, 1937. He attended Hebrew school at Talmud Torah in Richmond Hill; his bar mitzvah was held there on March 4, 1950, the fifteenth day of Adar.

He had an IQ of 154. His grades at John Adams High School ranged from 85 to 95 in most subjects?excepting Hebrew. In adolescence, he became intense, even faintly hysterical, playing every game as if his life depended on it, breaking into a sweat if he feared he was losing. His classmates mocked him constantly. He was always getting into fights. He talked compulsively of his ambition to enter West Point and filled his notebooks with sketches of soldiers and tanks. He even enlisted in the National Guard while still in high school, wearing his uniform to class on drill days.

But his obsession became even stranger in his junior year, about three years after his bar mitzvah, when he began filling his notebooks with German tanks and papering his bedroom walls with photographs of German generals.

He never applied for West Point. Instead, after graduation in 1955, he enlisted in the Army. He told one friend that if he couldn't become a soldier, he had nothing left to live for. Burros was an inept paratrooper: overweight, poorly coordinated and slow. He wore thick-lensed glasses that made his eyes look larger than they were. The other guys in the barracks laughed at him. He had no friends. Finally, he made three phony suicide attempts: a few shallow razor cuts on the wrist; an overdose of aspirin; and again the razor. He left at least one suicide note praising Adolph Hitler. The Army discharged him "by reasons of unsuitability, character, and behavior disorder."

After his return home in 1958, Burros worked as a printer at the Queens Borough Public Library. Though a diligent, conscientious employee, he talked of nothing but his admiration for Hitler and his hatred of Jews. His parents knew. They prayed it would go away. In his spare time, Burros operated the one-man American National Socialist Party from a post office box in South Ozone Park. He rubber-stamped swastikas onto his letters; distributed fliers such as "There's Nothing Wrong with America That a Pogrom Wouldn't Cure." He preached that "the Jews must suffer and suffer and suffer."

In 1960, Burros moved to Arlington, VA. He lived at the headquarters of the American Nazi Party, where the rug was an ark curtain from a synagogue. He swore an oath of loyalty to Adolf Hitler and to George Lincoln Rockwell, the American Nazi leader. That was around ten years after his bar mitzvah, when he had become a man and assumed a man's responsibilities to his family and his people. Burros's fanaticism and skill as a printer raised him from the ranks. He became the party's National Secretary?its third-highest office?and received the Party Merit Medal. He was arrested four times for disorderly conduct and received a suspended sentence for vandalizing the Anti-Defamation League.

Around this time, a friend painted his portrait in oils. Behind Burros, portrayed in full uniform, rose the smokestacks of Auschwitz. He often carried a little bar of soap, wrapped in green paper bearing German words meaning "Made from the finest Jewish fat." As George Thayer wrote in The Farther Shores of Politics, Burros usually sat with his knees up under his chin, hooking his boot heels on the edge of his chair, while cocking his head to one side and giggling like a teenager. When he was excited, the giggle became uncontrollable. Party comrades mocked his waddle?Rockwell called him "the ruptured duck"?which wore out the sides of his boot heels. He was always asking Rockwell for money to buy new heels.

Within eighteen months, Burros began doubting Rockwell's destiny. After all, in the party's early days, before the Commander began raking in fees from the college lecture circuit, the storm troopers largely lived on corn flakes. On Nov. 5, 1961, Burros slipped out a window and returned home.

While working at a Manhattan printing company, Burros joined other dissident Nazis in founding the American National Party. It published Kill! Magazine from its headquarters, a wooden shack at 97-15 190th St. in Hollis, Queens. Burros signed its first editorial, "The Importance of Killing," and called on the white race to "Kill! Kill! Kill!...build a mound of corpses of traitors from which you can glimpse the great future." Burros demonstrated outside movie theaters showing Exodus. No one paid attention. The party and the magazine folded within a year or so.

Burros then hung out in Yorkville on Manhattan's Upper East Side. Long the center of New York's German community, this neighborhood had been the base of the German-American Bund before WWII and, according to Rosenthal and Gelb, remained a mecca of the extreme right. He finally joined the National Renaissance Party, a local fascist group with links to Arab regimes and South American Nazi exiles. Burros was dissatisfied: James Madole, the NRP's anemic, asthmatic leader, didn't favor killing all Jews.

In July 1963, the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) demonstrated against the White Castle diners, claiming they discriminated against negroes in hiring. Various rightists counter-demonstrated, calling the demonstrators "niggers" and "coons." On July 13, 1963, about a half dozen NRP supporters drove to a CORE demonstration at a White Castle in The Bronx. One of Madole's men shouted, "Let's get out of here, it smells like a zoo." Another roared, "What do you expect when there's nothing but niggers."

A picketer leapt at them. The cops broke it up. Three NRP men drove to the 43rd Precinct, complaining that the demonstrators had assaulted them. Then a detective noticed the fully loaded .22 caliber revolver, loaded teargas guns, crossbow loaded with a steel-tipped arrow, butcher knife, switchblade, straight razor and axe in their truck. He arrested the counter-demonstrators; Madole and Burros were picked up later that day. In May 1964, a jury convicted Burros of conspiracy, riot, and firearms possession. His family bailed him out pending his appeal.

Believing Madole to be a mere windbag, Burros quit the NRP. He briefly published The Free American?"The Battle Organ of Racial Fascism"?which he dated "YF76." YF meant "Year of the F" as counted from the birth of Hitler. In early 1965, he attended a revival of D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation at the Museum of Modern Art. It inspired him. He resumed an acquaintance with Roy Frankhouser, the one-eyed rabblerousing Grand Dragon of Pennsylvania, who introduced Burros to Robert Shelton, the Imperial Wizard. Shelton almost immediately appointed Burros the Grand Dragon of New York, ruler of several dozen Klansmen, organized in two Klaverns: one in Yorkville, another on the waterfront.

In 1965, the House Committee on Un-American Activities subpoenaed Sheldon, and identified Burros and other Klansmen. This made the papers. Burros was soon fired. The stories were also noticed by a government agent who, having investigated Burros, knew his parents were Jewish. According to Rosenthal and Gelb, the agent had not realized Burros was still an anti-Semitic activist. He concluded Burros could be stopped only by his exposure as a Jew and telephoned a friend who knew someone at the Times.

A Jewish Klansman is news. The editors assigned the story to Phillips on Fri., Oct. 22, 1965. While he checked out the leads, two other reporters, Steve Roberts and Ralph Blumenthal, did the legwork. Phillips tracked down George and Esther: they wouldn't talk. Over the next week, the paper tracked Burros' life from high school through the Army to the fringe groups and magazines. They found the record of his parents' marriage. But the reporters needed one more fact to prove that, on at least one day of his life, Burros had committed himself to being a Jew.

When Burros threatened Phillips in the luncheonette, the reporter called for the check. They stepped outside and Burros threatened Phillips again. The Timesman, a devout evangelical, replied, "It is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment." Burros said he was trapped, couldn't change, and liked his life. Then they shook hands, and Burros waddled away.

On the next day, Sat., Oct. 30, Blumenthal and another reporter, Irving Spiegel, went to nearly every synagogue in Richmond Hill and Ozone Park. Just before their 2:00 p.m. deadline, Spiegel confirmed the bar mitzvah at Talmud Torah and phoned the desk.

On Sun., Oct. 31, 1965, Dan Burros was at Frankhouser's residence in Reading, PA. He went out early to buy the New York Times and apparently returned without reading it. Then he looked at the front page and gasped, "Oh, my God." He ran upstairs with Frankhouser and several other Klansmen just behind. Burros hurtled into Frankhouser's bedroom, grabbed a .32 caliber revolver from a bureau, and turned to his friends.

He said, "I've got nothing to live for," and fired into his own chest. Frankhouser's girlfriend screamed. Then Burros, still standing, said, "This will do it," and, raising the gun to his head, pulled the trigger.

Some later objected to the decision of the Times to run the story. This was sentimentality: Burros was a public figure by choice and therefore fair game. Anyway, Frankhouser called the Reading police, and the coroner pronounced Burros dead later that morning. The Reading police called the NYPD. The NYPD called George and Esther Burros. They caught a late bus, missed a connection at Philadelphia, and sat up all night in the terminal. They arrived in Reading the next morning. On their way to the hospital to identify the body, Esther said, over and over, "He was such a good boy."