Imagining Greenwich Village in 2031

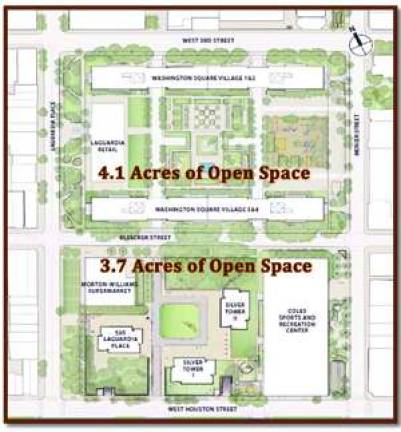

Residents, politicians, activists envision impact of NYU's long-term expansion plan New York University scored a key victory last week as the City Council approved a slightly scaled back version of the school's controversial 2031 expansion plan. While the project was pared down, it will still add close to 6 million square feet of academic space throughout the city. Nearly half of the expansion, equal to about the size of the Empire State Building, would be concentrated on two Washington Square-area superblocks located near the school's main campus in Greenwich Village. The NYU plan calls for four new buildings on the two large blocks bordered by LaGuardia Place and Mercer, West Houston and West 3rd streets. The buildings will be used for both academic and residential purposes. The plan has generated an enormous amount of discussion and controversy both for and against since it was unveiled by NYU officials in 2010. Moreover, the Council's approval comes at a time when residents uptown are waging a battle of their own against Columbia University's mammoth, long-range plan in West Harlem that includes a 17-acre, $6.3 billion campus expansion. Opponents of the NYU plan, including village residents, activists, NYU faculty members and others, have already vowed to continue the fight, including an expected legal challenge, to get the plan sent back to the drawing board and significantly revised. The plan has the support of the mayor and is unlikely to be vetoed. But what if the current incarnation of the plan is upheld and remains largely unchanged? What will Greenwich Village look like in 2031? Will it be congested, overcrowded and largely unlivable, as many naysayers suggest, or will the plan usher in a new chapter of peaceful coexistence between NYU and its Village neighbors? "When I ask myself what the Village will look like in 20 years, the first thing I see is large, concrete, functional-looking buildings casting long shadows over the neighborhood; absorbing all the light. The only outdoor space for people to congregate will be Washington Square Park, and you know how crowded that gets now!" said Janet Hayes, who lives in a high-rise co-op at 505 LaGuardia Place near Houston. A longtime resident of the Village and a local Republican leader, Hayes predicted that NYU's plan, if allowed to come to fruition, would greatly affect life in the Village and not in a good way. "Take grocery shopping, using the dry cleaner or going out to dinner, for example-full-service restaurants will be replaced with beer halls, pizza places and other fast-food sources," Hayes predicted. She added that more stores would cater to NYU and transit would be a "nightmare"; subways and buses would be overcrowded all day long, and "forget catching a cab." In support of NYU's plan, Borough President Scott Stringer, who most recently helped to broker concessions from the school, cited substantial economic benefits for New York City, which include the creation of 9,500 permanent jobs and as many as 18,200 construction jobs over the next 20 years. Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, has been one of the plan's most outspoken critics and has worked to help mobilize village residents, activists and like-minded politicians in opposition to a project he has called a "grandiose scheme of a private university's super-rich board and its president." Immediately following last week's Council vote, Berman said in a press release, "The NYU expansion plan will turn a residential neighborhood into a company town and subject it to 20 straight years of construction." Robert Yaro, president of the Regional Plan Association, a nonprofit planning organization that serves the tri-state area, however, said NYU's expansion is important to the city for many reasons. "NYU's continued success is vital to the economy of New York. The university is among the city's largest private employers," Yaro noted. "NYU can continue to attract top students and scholars only if it is able to modernize and expand?By emphasizing density, the NYU plan will avoid harming any of the Village's historic fabric." Asked about possible loss of open space and congestion resulting from NYU's plan, Council Member Margaret Chin seemed confident the issue has been addressed. "Under this plan, the open space on the superblocks will be improved and it will be fully accessible by the public for the first time," Chin said in an emailed statement. "The padlocks and fences around the Sasaki Garden will finally come down, and this park-which few New Yorkers know about-will finally be open to the public. We will also gain a pedestrian walkway, or 'greenstreet,' behind the new Zipper Building, which will connect the Village with Soho," she said. The Council member added that the walkway would be lined with cafés and restaurants and would have an indoor atrium open to the public year-round. A spokesperson for Chin also noted that the university would be "bound" by a 500-page restrictive declaration document that specifies what the school can and can't do with regard to construction, building and other logistics related to the plan. For example, the school has committed to limit construction to the hours between 8 a.m. and 4:30 p.m. and to limit weekend construction. In addition, the school has promised to assist with construction mitigation issues related to air quality and noise by equipping affected apartments with soundproofing materials. "This plan is a way to start over. It is a pathway forward," Chin said. "This plan integrates the Greenwich Village community and NYU in ways that have never been done before." Terri Cude, co-chair of Community Action Alliance against NYU 2031 and a member of Community Board 2 (CB2), isn't so sure of the plan's integration into the neighborhood. "If NYU builds everything that is in the current plan, we will have a very dark neighborhood," Cude said. Asked about the various committees that were formed by NYU to address community concerns and incorporate residents' needs into the plan, Cude said, "They attended all the meetings and listened to everything we had to say. The only thing they didn't do is modify the plan at all based on the input." But the concessions brokered by Stringer in early April did in fact include a significant overall density reduction, preservation of public space as parkland, elimination of a temporary gymnasium on the site of two community playgrounds, elimination of proposed dormitories on the Bleecker Building and an affirmation of NYU's commitment to provide space for a K-8 school. Brad Hoylman, former chair of CB2 and candidate for state Senate in District 27, testified before the City Planning Commission back in the spring that the NYU plan would "forever alter the character of the neighborhood, bring in thousands of new people into the area [estimates suggest up to 12,000 people daily] and cause decades of construction disruption for local residents." Village residents and community garden members Marcia Lawther and Bob Hirschfeld moved to the neighborhood in the mid-1970s. "It's invasive. It's crowded enough as it is," said Lawther when asked about the expansion. "In the '70s, things were much quieter, there was not much going on," recalled Hirschfeld. "NYU was a separate world. It wasn't elbowing its way into the community." However, signs of hope for the future of the project were evident on Tuesday as legislators lauded a new agreement between NYU and the residents of 505 LaGuardia Place in an effort to maintain long-term affordability at the Mitchell-Lama development. "I am pleased a deal has been reached and much-needed affordable housing has been preserved in Greenwich Village," said City Council Speaker Christine Quinn in a prepared statement. "This agreement guarantees that 505 LaGuardia can maintain affordability and that the working-class families that currently reside there will be able to continue to live in a neighborhood they have long called home."