Foraging Through Central Park

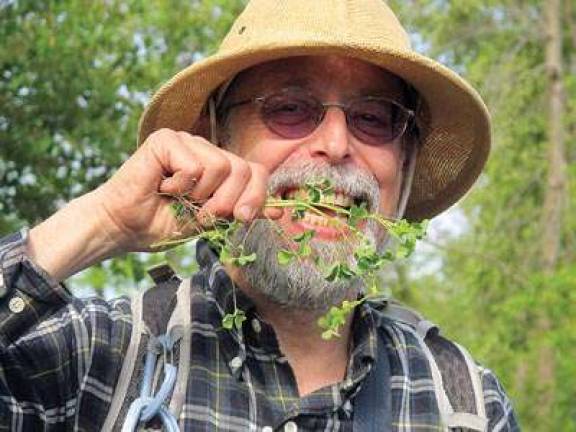

Steve Brill, a New York naturalist and vegan, began his 30th year of leading foraging tours in Central Park this spring. Equipped with a small shovel and an iPad to demonstrate how plants look at different stages of growth, he led about 30 New York nature enthusiasts on a recent exploration of the park's flora. The group found and collected about a dozen edibles, some of which had medicinal qualities. Among them were common blue violet (Viola sororia), a stemless perennial with heart-shaped leaves; yellow wood sorrel (Oxalis stricta), a low-growing plant with shamrock-like leaves and small yellow flowers; and poor man's pepper (Lepidium virginicum), which tasted like mustard. All three would be delicious in a salad and some are also good for making soups, Brill said. "They are weeds that reproduce themselves, and that's why we can eat them," he said, adding that people always used weeds for cooking. As the tour progressed, he cited historical anecdotes. Poor man's pepper got its name back in the days when real pepper was imported from Asia and thus was expensive. "People used it because they needed to cover up the taste of rotten food or starve to death," Brill said. "This is my apocalypse plan," said Sarah Anderson, originally from Utah and now a New York resident, explaining what drew her to the event. She added she was only half-kidding. Participants also chewed on vanillatasting flowers from a black locust tree and dug up sassafras roots as Brill shared a recipe for root beer. Ignacio Parkman, age 4, said "that lemony one was my favorite," referring to wood sorrel. Another participant, Bill Gallagher, found a plant Brill never saw growing in Central Park before: catnip. Brill also pointed out poisonous species to stay away from, such as white snake root (Eupatorium rugosum) with dark green opposite leaves. "It stops your brain from communicating with your heart and lungs," Brill said. Not everyone supports foraging in city parks, though. The New York City park authorities are concerned about residents harvesting from the parks, and have always been. In 1980s, Brill was arrested for foraging. Later he appeared on David Letterman's show, where he humorously described how he was handcuffed but eventually let go because he had "eaten all the evidence." The charges were later dropped and Brill was allowed to continue foraging, although there is no such thing as an official permit. "They just look the other way," he said. "We don't condone what he does," said Vickie Karp of the City of New York Parks and Recreation press office. She added that foraging can be dangerous. "Some plants can be poisonous," she said. There is also a concern that aggressive foraging may affect the park's natural habitats. "Every plant should be left in its place so that Central Park's 38 million annual visitors can enjoy everything about its landscapes while they're here," said Maria Hernandez, director of horticulture for the Central Park Conservancy. Brill emphasized that he teaches responsible foraging. He harvests plants that regenerate and digs up tree sprouts that won't grow because they are under a bigger tree. He also brings attention to poisonous species, including those that are edible early in the season or have to be cooked properly to dispose of the toxins. "I've been picking the same things in the same place for 30 years," he said. Brill does not have a degree in botany, but believes in reconnecting with nature. "I learned it all on my own," he said. "I'm a science geek." He leads foraging tours in other boroughs, Long Island, New Jersey and Connecticut. Originally from Queens, he now lives in Westchester. "There's plenty to eat there," he said.