No APs, no problem

Sure, I felt the panic at first. There was that moment before freshman year when I found out that, unlike my Stuyvesant or Hunter counterparts, I wouldn’t be able to take AP courses in high school.

There was alarm, concern about college applications. How would I compete against students taking “AP U.S. History” when my transcript simply read “U.S. History?” What good did my ‘A’ in “Intensive Biology” — whatever that meant — do when compared to a ‘5’ on the “AP Biology” exam?

It took me three years and a whole lot of testing to realize that the lack of AP courses is one of the best things about my school’s curriculum.

I attend the Ethical Culture Fieldston School, a private institution with an emphasis on independent thinking and “ethical citizenry.” In an attempt to better fulfill its mission, the school dropped all advanced placement courses in 2001, a decision that was heavily influenced by students and faculty.

Before graduating in 1998, student Matthew Spigelman wrote an essay for his English class encouraging the school to eliminate APs.

“While the goal of AP courses is to prepare students for the AP test, the goal of Fieldston-specific courses is to learn for learning’s sake,” he wrote. “Courses specific to Fieldston have curricula generated by Fieldston teachers. Thus, Fieldston teachers bring enthusiasm to the Fieldston-generated courses not generally found in AP courses.”

Spigelman’s proposal quickly gained support from teachers, and the program was eliminated within three years. Fieldston’s teachers took their expanded intellectual freedom and ran with it; students now enjoy a host of classes that many would not have been able to select with the pressure to enroll in AP courses.

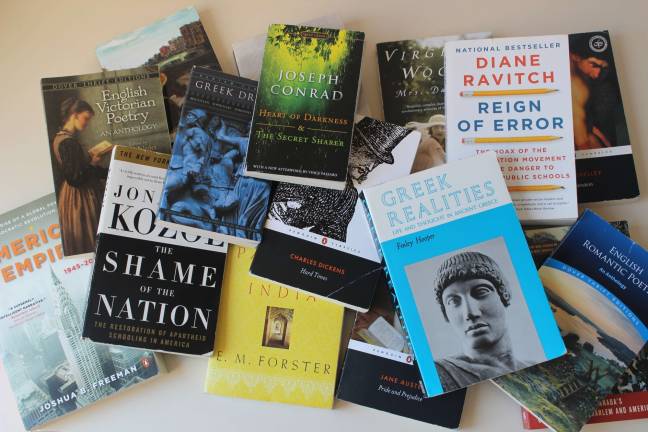

Instead of signing up for “AP English Language and Composition” simply for the AP credit, students choose from an extensive list of English courses including “Literature of War,” “Coming of Age Literature” and “Silence and Noise: The Politics of Storytelling.” Instead of “AP European History,” students can take “Contemporary Black Society,” “The Kennedy Legacy” or “The Ancient Greeks and Their Rivals.”

This fall, I will be taking “Revolución,” a class that explores the effects of the CIA’s presence in Latin American countries. Several of my friends will take “Hamilton: A Musical Inquiry,” designed by a history teacher after the sensational success of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway show.

How many students get to enter college with classes like “Animal Behavior” and “Chemistry of Food” under their belt?

Without the rigid structure of AP curricula, teachers are able to design niche courses that prioritize in-depth intellectual exploration and analysis, which many AP teachers have to sacrifice in order to cover the breadth of topics assessed on the AP tests.

Some of my favorite and most effective teachers have been those who constantly adapt their syllabi to best meet the needs of their students, who allow students’ questions to direct class and who don’t mind devoting a period here and there to a classroom discussion on current events.

What is gained from these lessons is not information that will be tested on a final exam, but knowledge that is relevant to our everyday lives and critical skills that will guide us through our future education. Rather than have students cram for the College Board’s exams and soon forget the material, these focused and flexible courses facilitate deep learning. As Spigelman wrote, we should be learning for the sake of learning, not for yet another test.

My classmates and I are lucky to attend a school that values students’ curiosity and teachers’ intellectual freedom so highly. We are even more lucky to have teachers who are so creative and devoted to giving us the best possible education that they generate relevant and engaging material year after year.

But, of course, students still want to be able to attend their top choice colleges. The administration also wants this. Before implementing the new policy in 2001, Rachel Friis Stettler, Fieldston’s Upper School principal at the time, and faculty in the college office contacted selective colleges to make sure that it would not harm the students’ chances for acceptance.

The response was unanimous and clear: We support your decision, and your students’ applications will not be affected.

Sure enough, when the Class of 2002, the first to graduate without taking any AP classes, sent out applications in the fall, Fieldston saw its highest early acceptance rate in many years. Anyone who has read the ‘College Destination’ sheet posted on the school website or who happens to be on Facebook on May 1, when seniors traditionally announce their college decisions, can confirm that students have not suffered without AP scores on their transcript.

Since 2001, several other New York City schools, such as Dalton, Riverdale and Spence, have followed Fieldston’s example.

This is not to say that replacing AP classes with teacher-designed ones is a viable option for all schools; many have neither the resources nor the teachers to effectively do so.

So, my argument extends only to schools that do have this option. For these, I urge the shift away from APs toward focused classes centered on student learning, not test taking.

And, finally, for those students (and parents) who are worried about missing out on standardized testing experience, be assured that the SAT, ACT and Subject Tests are enough to make you pray to never see a multiple choice bubble sheet again in your life.

Trust me on that one.