sendak on stage

Who doesn’t love Maurice Sendak? His books have sold more than 30 million copies and been translated into 40 languages. His fuzzy, funny characters — human and animal alike — have enchanted children and adults of all ages. Say “Let the wild rumpus start!” and everyone gets it.

But Sendak’s treasured picture books, “Where the Wild Things Are” (1963), “Chicken Soup with Rice” (1962), “In the Night Kitchen” (1970), and “Outside Over There” (1981), are just part of the narrative. It turns out the award-winning storyteller and illustrator, winner of the Caldecott Medal (1964) and the National Medal of Arts (1996), took a break from the book game in midlife and began working collaboratively to produce opera and ballet, around a dozen works in all.

Designs for his five most important productions, “The Magic Flute,” “Nutcracker,” “Wild Things,” “The Love for Three Oranges” and “The Cunning Little Vixen,” are presented in the current show.

Word to the wise from Sendak, who was born in Brooklyn to Polish Jewish immigrants and once worked as a window dresser for F.A.O. Schwarz: “Fifty is a good time to either change careers or have a nervous breakdown.”

Maurice and His MuseThis is the fourth Sendak-themed show at the Morgan, with nearly 200 items detailing the adaptation of his work and other classics for the stage. There are critter costumes, animal props, mechanical toys, drawings, watercolors, dioramas and storyboards, the latter like comic-strip panels and typically reserved for films and television.

Sendak had a special relationship with the Morgan, an institution he revered and bequeathed more than 900 drawings to after his death in 2012, at 83. Some 150 are on view here. He studied works in the collection by William Blake and Tiepolo — both Giambattista and son Domenico — and incorporated them into his oeuvre.

The exhibit features a rare side-by-side comparison of an original score by Mozart belonging to the Morgan and a Sendakian send-up, a so-called “fantasy sketch” of the composer clowning around on the staves of a musical page.

“It’s impossible, it’s difficult to find the words, you’re looking at the real thing ... you are with him at the moment when he is composing,” the self-described “Mozart freak” enthused to PBS in 1987, as he handled manuscripts by his 18th century muse.

So it is only fitting that the exhibit kicks off with Sendak’s designs for the costumes and sets of the Houston Grand Opera’s production in 1980 of Mozart’s “Magic Flute,” his favorite opera.

Sendak’s visual take on the classic is “an irreverent mash-up of styles,” an essay in the catalog states. The designs have their origins in drawings by Blake at the Morgan, Egyptian imagery inspired by the “Treasures of Tutankhamun” blockbuster at The Met in 1978, the engravings of German Romantic artist Philipp Otto Runge, Art Deco and more.

Music is a BalmAt the same Sendak was designing the opera, “Outside Over There” was gestating. Curator Rachel Federman points out the thematic crossover from opera to book, writing in the catalog: “Just as Tamino, the protagonist of Mozart’s ‘Magic Flute,’ mollifies wild animals and endures Sarastro’s trials by playing his flute, the book’s heroine, Ida, plays her wonder horn to subdue the goblins who have stolen her sister.”

In other words, music is a tonic, a balm. In Sendak’s world, it’s more important than pictures, the curator argues, which is why the author was so drawn to opera, essentially music and words, in the latter part of his career.

The great illustrator undoubtedly had Blake on his mind when he created the finale backdrop for Mozart’s jewel, “Design for Temple of the Sun,” 1979-80, on display. The rainbow, the coloration — pale pinks, blues, yellows and greys — are strongly indebted to the English Romantic’s watercolor, “Milton’s Mysterious Dream” (ca. 1816-20), also on view and also seen by Sendak during a visit to the Morgan. Blake’s influence is evident from the get-go, in both the early drawings and the storyboard.

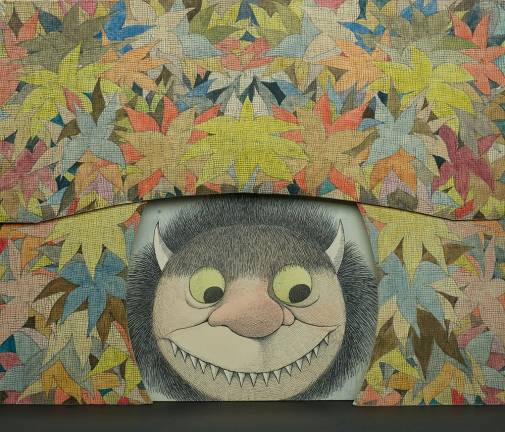

Wild IndeedJust two weeks after the opening of “The Magic Flute,” a one-act opera based on “Where the Wild Things Are” premiered in Brussels on November 28, 1980, with both libretto and costume/set designs by Sendak. The production was incomplete and plagued with technical difficulties. The costumes for the Wild Things were hard to maneuver and to breathe in, and one Thing fell into the orchestra.

A subsequent staging by the Glyndebourne Touring Company in 1984 ironed out the kinks and assigned three handlers to the costumes: two off-stage and one who inhabited the monster outfit and controlled the movement of all body parts save the eyes, which were operated via remote control.

As the works on paper suggest, Sendak was clearly in his element creating for “Wild Things.” The costume studies for Max in his wolf suit, Mama cum vacuum cleaner and those Things include hand-written notes.

The most explicit instructions were reserved for the Wild Things costume sketch, dated 1979, which visualizes a boy inside a monster getup. Witness the dualism, the yin-yang: boy-beast, beast-boy. Each exists within the other. It’s not an easy part to play: “Singer must hear and see peripherally ... There must be enough air for singer to breath [sic]”

And so on.