native innovation for the next generation

BY ALIZAH SALARIO

Touch, don't just look: at the new imagiNATIONS Activity Center at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian, children are encouraged to handle objects originating from across the Americas, from the Arctic down to Tierra del Fuego.

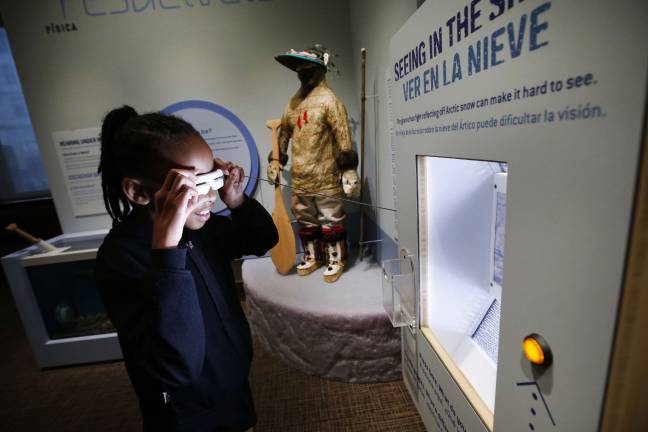

On May 19, as part of the Museum's annual Children's Festival, the city's youngest residents broke in imagiNATIONS, a multimillion-dollar sensory extravaganza that showcases the innovations of Native peoples throughout the Western Hemisphere. Children plucked the nylon strings of a Charango, an instrument made from an armadillo shell and played by the Aymara people of the Andes. They studied different types of corn, and used a touch screen to raise enough crops to feed a family of four while learning about the technology used by indigenous farmers in Mexico to develop maize. They sat in a kayak replica to appreciate the science behind its structure, (carefully) tossed a Lenape football made from tanned deerhide and deer hair stuffing — and tested out a pair of Arctic sunglasses that resemble the sporty wraparounds worn by modern snowboarders to protect against the harsh glare of sun on snow.

“I'm hoping people walk away from here with a different perspective, and realize that Native people are still contributing to our lives today,” says Gaetana De Gennaro, manager of imagiNATIONS.

At a time when questions about who shapes and transmits history are being raised, the imagiNATIONS center is a, well, innovative answer. De Gennaro notes that Native cultures are often taught as a “laundry list” of traits and tasks, and though science and technology is central to Native cultures, it is not often central to the narrative.

The Museum seeks to change that. Native scientists contributed their research and expertise to the creation of imagiNATIONS, and De Gennaro, who is part of the Tohono O'odham tribe of Southern Arizona, is responsible for curating the 120 Native objects in the center's discovery room. From lacrosse sticks to woven baby carries that rival the construction of the modern Ergobaby, these objects reflect innovations from across the Americas and the Caribbean.

“We really want to have people realize that Native science continues,” says De Gennaro. “Contemporary Native people are in the sciences; they're mathematicians, they're doctors, they're astrophysicists. They're all over the place, still working on science, trying to better our world and figure things out that we don't know about.”

Joint funding for the sleek activity center came from the Mayor's Office, the New York City Council and the Manhattan Borough President's Office through the Department of Cultural Affairs. Tom Finkelpearl, NYC Department of Cultural Affairs Commissioner and co-chair of the Mayor's Commission on Monuments and Markers, spoke about the importance of New York City history — and the way that history is told.

“I think there's been a re-evaluation, a looking in the mirror to understand how we've told history. It's been a great moment for myself and other people to reset, in a way,” he said.

The Museum sits upon the tip of Manhattan, and in fact it does rewind the history of this storied piece of land to a point long before it was christened New Amsterdam. Objects from the Lenape tribe, indigenous to the region, are on display and then fast-forward a few centuries. A segment of steel cable from the Bayonne Bridge is on display next to a replica of the Q'eswachaka Bridge in Peru, comparing striking similarities and tensile strength between New York steel and braided grass rope of the Quechua people.

“It's really to have people realize the continuity of native knowledge. It's part of your daily life, from the foods you eat to lacrosse,” says De Gennaro. It was Amazonian people who invited a chemical process to create rubber long before vulcanization, and the Aztecs who developed chocolate from the cacao seed.

While imagiNATIONS is geared toward 12-year-olds, most of the kids at the inaugural weekend were under nine years of age. This reporter brought a very discerning patron, her one-year-old daughter, who delighted in the texture of horse hair and alpaca pallets. It's too soon to tell, but learning through sensory engagement that shows how the past is very much a part of our present may be the way the littlest New Yorkers begin to build a more inclusive history of our city, and beyond.