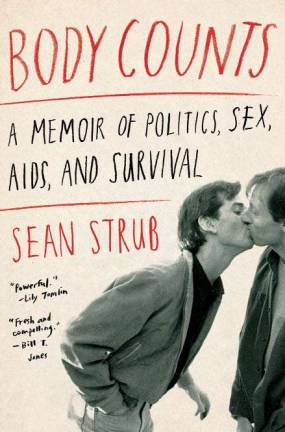

Walking with Village Ghosts

A chronicler of the AIDS fight revisits his downtown battleground

My new book, "Body Counts: A Memoir of Politics, Sex, AIDS, and Survival," is about 35 years of my life on the frontlines of LGBT and HIV activism, which coincides with my time in New York. I moved to the city in 1979 and have lived all over lower Manhattan: both 23 and 227 Waverly Place, 3 Milligan Place, 58 East 11th Street, 450 West 58th Street-and, for many years, a loft at 349 West 12th Street where I founded and operated POZ Magazine.

The West Village was not only an epicenter of the epidemic, but it was also where major empowerment movements for people with HIV were fomented and developed. In 1987, when Larry Kramer called for a unified response to the death and dying, launching ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, it was at the LGBT Community Center on West 13th Street, where the group continues to meet every Monday night.

But before there was ACT UP, there was PWAC, the People With AIDS Coalition, and it, too, was born in the West Village. Finding PWAC not only changed my life ? it saved it.

***

In November of 1985, the New York Native reported that the People With AIDS Coalition had opened the "Living Room," a small office and drop-in center. A few weeks before, I had received my HIV-positive diagnosis. I was floundering, terrified, uncertain what to do. Out of desperation, I had to visit.

The Living Room was on tree-lined West 11th Street in a space provided by St. John's in the Village Episcopal Church. I pushed a buzzer aside a wrought-iron gate and a raspy buzz unlocked it. A tunnel-like horse walk ended in a garden, still gorgeous with lush plantings, despite the time of year. The garden was reflective of PWAC itself, vibrant and full of life. Tentatively entering the place, I found it was a literal living room, crowded with flea-market rejects chairs and couches.

Every surface was piled high with gay newspapers, medical journals, and AIDS pamphlets. A balding man with glasses was on the phone at a makeshift desk. When he finished the call, he stuck out his hand. Michael Hirsch launched into a well-rehearsed spiel on how PWAC was comprised of people with AIDS supporting other people with AIDS, their newsletter, board structure, and fund-raising -- before I even asked a single question.

Hirsch filled my knapsack with AIDS reading material. As I read the literature, I realized the voice of PWAC's membership was thoughtful, practical, and often funny. They had no interest in pity, which was what I had mostly encountered since my diagnosis.

One day at PWAC, I ran into Joe Foulon, a friend I had dated briefly years earlier. Joe was stunning: thick, straight dark hair and perfect skin, with amazingly high cheekbones. He was one of those genetically blessed men who turned heads wherever he went. If he hadn't been so modest and kind, Joe would have been easy to dislike.

Seeing him was a relief-he was alive!-but then I saw a postage stamp?size purple spot in the middle of his forehead, like a permanent tattoo of Lenten ashes. Kaposi's Sarcoma, a cancer of the blood vessels often visible on the skin, was the scarlet letter of AIDS. The KS lesion was an imperfection that gave him an appealing vulnerability.

Joe was on PWAC's board. In 1983, he had helped launch the National Association of People with AIDS. I was impressed. Hearing how involved he was in fighting AIDS made me realize how little I had contributed. I felt like I had been asleep while this tragedy was unfolding around me.

A few months later, I invited Joe to join me at a big party at my boyfriend André Ledoux's loft on East 11th Street, just off University Place. It was crowded and noisy, and the loft had no air-conditioning. At one point, Joe and I climbed through a window and sat on the fire escape to cool off and talk quietly. We held hands, watched the night sky, and listened to the muffled sounds of music and laughter coming from inside.

"Doesn't it seem like a really long time ago that we met?," Joe asked. "It's a whole different world now." We were quiet for a minute, and then I said, "It seems like everything has changed."

***

For those of us who survived that era (Michael, Joe and André did not), none of us can travel the West Village without walking in the company of ghosts.

Sean Strub is an activist, writer and executive director of the Sero Project, which combats the criminalization of people with HIV. To order Body Counts, visit www.SeanStrub.com