Touring the Gay Ghetto

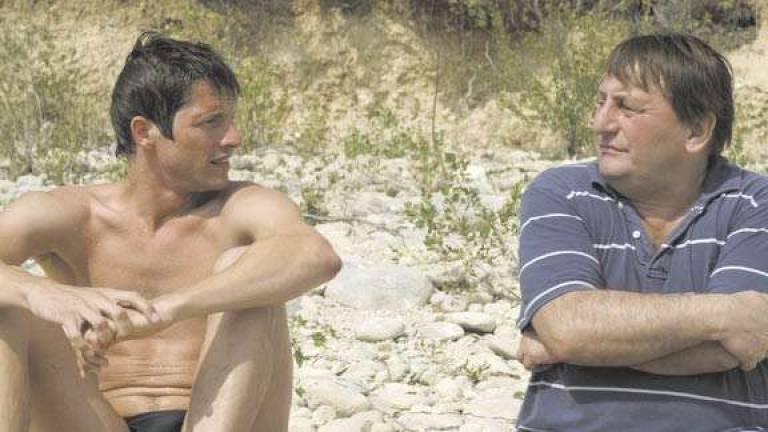

The cruisey beach setting of assorted gay types suggests a behavioral grid--including bi-curious divorce Henri (Patrick D'Assumcao), a burly Gerard Depardieu-type who cagily pursues Franck through casual conversation. The murder investigation by a local police inspector (Jerome Chappatte, who resembles Jean-Luc Godard) provides cursory suspense while analyzing that grid-it implies a critique of how social authority ineffectually responds to the mysterious, uncontrollable impulses of gay male sex.

Many critics have superficially likened Stranger by the Lake to Hitchcock and although the element of erotic threat resembles Hitchcock's Suspicion and Rear Window, Guiraude's beach is really Francois Ozon territory--the sexual obsessiveness that the ever-adventurous Ozon, student of Cocteau and Fassbinder, has lately surpassed. (Ozon's In the House was a 21st century Rear Window and a more satisfying film than this.)

Guiraude began as a student of Godard demonstrating an estheticized sense of humor in his 2001 medium-feature That Old Dream that Moves, where his prankish ellipses observed the private thoughts of laborers assessing their working conditions while contemplating a strike. Stranger by the Lake's tour of gay sex habits is also full of ellipses, surveying psychological games within gay men's amatory pursuits--various, private needs from physical release, love-of-danger, to simple fraternization. Guiraude's analytical style is not enhanced by the murder-mystery plot; if anything his bravura frankness, including the unnervingly quiet primal murder scene (like Leave Her to Heaven) drags gay film progress back to the pathological closet of Gregg Araki's aberrant feature, the self-loathing Mysterious Skin.

The Police Inspector's investigation suggests the potential for social assimilation and regulation through solidarity and compassion. But then those hopes are cruelly, doubly dashed--a nihilistic turn that prevents Stranger by the Lake's subculture from integrating into the moral universe. Integration is what Ozon learned from the example of Fassbinder's films that argued for the stabilizing universality of queer emotion. In Fassbinder's masterpiece Querelle, the interior (imaginary) gay world was seen with more rigor, passion and depth than Guiraude's leisurely, outdoorsy, out-of-the-closet tour of a spiritual ghetto.