The Public School Paradox

As the Upper West Side has gentrified, its public schools like dozens of others throughout the city have become much less diverse.

Not long ago, New York City parents sent their kids to public school knowing that they would be exposed to a student population as diverse as the city itself.

On the Upper West Side, that experience is disappearing.

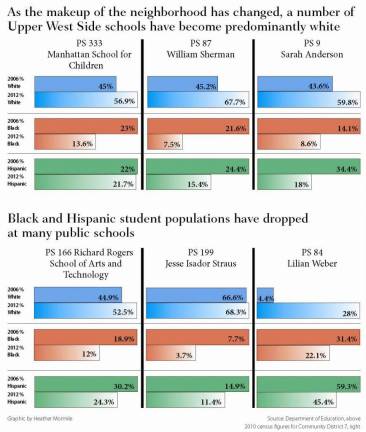

A West Side Spirit review of Department of Education data shows that in many parts of the Upper West Side, diversity in public elementary schools has dropped dramatically, as predominantly white schools have become even less diverse and black and Hispanic students have left the neighborhood.

At P.S. 87 on W. 78th Street, for instance, the black student population has dropped to a third of what it was six years ago.

"When my kids went to P.S. 87, the diversity was a microcosm of New York City, and that's one of the reasons I loved the school," said Andi Valasquez, whose two daughters are now in high school. "It's still a good school community, but the diversity is just no longer there."

The school pulls mostly from zoned students within the district, which runs from West 72nd to West 80th streets, from Central Park to the Hudson River. Like many parts of Manhattan, that slice of the Upper West Side has become more upscale as real estate values have soared, pricing many families out of the neighborhood.

Black and Hispanic families have borne the brunt of those changes. According to U.S. Census data, the total white population in Manhattan's District 7 has increased, while the black population has decreased 15% and the Hispanic population has dropped 10%.

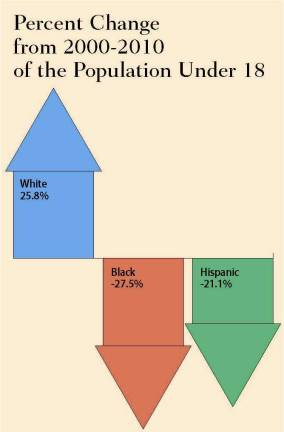

Among school-aged residents, the numbers are even more striking. The number of white kids in the district is up 26% -- thanks to an influx of young families ? while the number of black kids under 18 is down 28% and Hispanic kids are down by 21%.

All of that means the situation at P.S. 87 is hardly unique. Almost half of the schools on the Upper West Side had a more-than 25 percent gap between numbers of black and white students.

"I think that what happened in Manhattan is gentrification of the elementary and middle schools, and you're seeing increasingly neighborhood schools," said Clara Hemphill, editor of Inside Schools and author of New York City's Best Public Elementary Schools. "The affluent neighborhoods used to be whiter than the schools. Upper middle class white people with children are increasingly staying in the city rather than moving to the suburbs."

A number of factors, from the recession to better public school options have shifted wealthy parents toward public school options citywide, when they would have normally gone for private schools, said Noah Gotbaum, a member of Community Education Council 3, which encompasses the Upper West Side. In addition, said Gotbaum, adding charter schools to the mix has only further shifted the balance of diversity. This leads to overcrowding in the schools, and the likelihood that a public elementary school will reflect the population of the surrounding neighborhood, rather than the desire of the parents to have their children experience diversity.

On the Upper West Side, for instance, over 63 percent of children and teenagers under 18 are white. On the Upper East Side, the under-18 population is over 75 percent white. By contrast, on the Lower East Side, over 70 percent of underage residents are either Hispanic or Asian.

Given the demographic data, maintaining any semblance of diversity at these schools can be hard work.

At P.S. 75, on the Upper West Side, the parents' association has worked to help create one of the more diverse schools on the Upper West Side, with 16 percent white students, 27 percent black students, 52 percent Hispanic students and 5 percent Asian students.

Katherine Sprowal, who is on the PTA at P.S. 75, and whose son is in fifth grade, said the school makes an effort to aggressive recruit students from throughout the district ? not just the kids who happen to live in the boundary of the school.

"If there isn't a conscious effort made from every level within the school, from administration and PTA, then organically a lot of the schools could turn mostly white," she said.

Sprowal, a black parent, remembers that when she was considering private schooling for her son, the private schools were clamoring for him because they were looking to create diversity in their student populations.

Besides campaigning in each individual school, one of the many options being considered in CEC 3 to address the diversity issue is "Controlled Choice," a program by Michael Alves, an education consultant, who has implemented over two dozen versions of his program all over the country. Under the system, parents have more of a say as to where their child goes to school.

The program was originally designed as a way to increase racial and socioeconomic integration. Alves has found that when given the freedom of choice, integration will come more naturally. Alves is currently working with CEC 3 to come up with a pilot program for New York City, though he has not yet approached the DOE with a plan.

Even if Controlled Choice is not implemented in the foreseeable future, educators, parents and advocates across Manhattan agree that something needs to be done to slow the spread of unofficial segregation in schools.

"This is the real world where children won't just see people of just one race, students should be able to expand their communities and their worlds," said Teresa Arboleda, who is also on the CEC 3 board.