Sad-eyed Boy of Liverpool

John Kirby makes art out of crying

Some artists paint from the eye in the classic phrase. John Kirby's work derives from the lacrimal gland as much as the imagination. His sad portraits of people who seem already defeated in their internalized desire to connect can make a visitor weep as well as applaud. His paintings elicit tears without ever exactly dipping into sentimentality or its opposite, cruelty. The Liverpool-born Kirby seems to combine the two perspectives; for him they are both empathetic attraction and abhorrence in retreat-and yet fascination holds one there, same as it compels Kirby to focus his eye and imagination. His steadied palette of nearly monochrome sophistication and control is the evidence of keen study and intense concentration.

These are not only portraits from the eye, awash in sympathetic attention; they are also portraits that show delight in imagining the depths of the subjects' feelings. Kirby wants us to feel as his subjects feel-a hurt that humanizes, perhaps to the point of healing.

One favorite is Head from 2009, an oil on canvas portrait of a bald man's head with a lit candle wit protruding from his cranium as he sits, looking forward yet downward. He is both sad and contemplative. Kirby's idea is the inverse of the proverbial comic strip image of a light-bulb shining above a head that denotes the flash of an idea; here Kirby depicts the inner light of a mind that doesn't rest, even in quiet or in solitude. There is a light that burns and emerges from all of us, easy to be seen if we can handle its significance.

Kirby's sensitivity can be tactile as in an untitled 2010 clay sculpture-a simple piece it's a roughly molded head almost cradled in the palm of an equal-sized hand. Thinking is feeling Kirby seems to be suggesting. It is a comical approach to Rodin's The Thinker with lots of thought given to the slope of the forehead, the dim rouge of the slightly parted lips and the slitted eyelids closed-forced closed as if grimly keeping a secret.

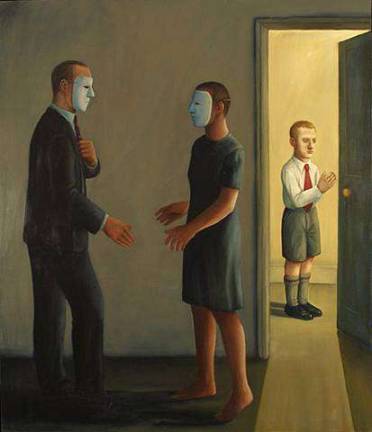

That secret may derive from the 1989 genre study Nightwatch where Kirby shows a father and mother wearing white masks just like the Untitled head; they're in private adult discussion while a small child stands in an open door at the right of the canvas, eavesdropping. The child's bright room contrasts the adults' gray area. Kirby's idea of innocence is also delightfully unsentimental.

In Falling Man from 2007, Kirby takes the once popular subject of Robert Longo's large scale body graphics and shrinks them to a 100x 70cm full color cameo. It is also fully comic, the human condition in free fall circumstances that evoke Magritte with its blue-sky backdrop. It is a humorous lament, sad yet buoyant which sums up Kirby's singular style of painting and feeling.

John Kirby at Flowers Gallery, Sept. 12 to Oct. 12, 529 West 20th Street