Remembering the Yippies

Counter-cultural haven on Bleecker Street still alive despite legal struggle

The Yippie Museum was cold on a recent Wednesday night, the kind of place you keep your coat on. A lonely bottle of Seagram's scotch sat behind the bar but nobody was pouring. Pot clouds lingered in the middle of the room, as 50 or so aging hippies ? along with a smattering of younger folk ? waited for the festivities to begin.

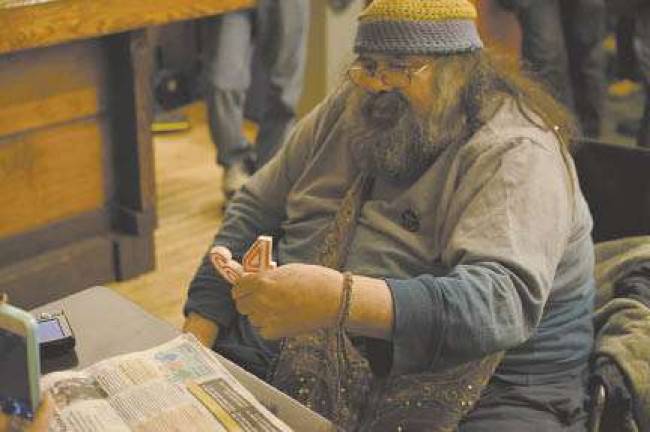

They were there to celebrate the 64th birthday of activist Aron Kay, the Yippie Pieman, so named for his penchant for hurling baked goods at those he's strongly disagreed with throughout his decades-long activist career, including William F. Buckley Jr. and Phyllis Schlafly.

Yippies ? shorthand for members of the Youth International Party ? took turns at the mic regaling the crowd with stories of how they met Pieman and the various exploits embarked upon by the organization. Leftist, anti-nuclear, anti-war, pro-marijuana, the Yippies ? founded in New York City ? have been politically active since the 1960s.

In 1973, Dana Beal, a Yippie pro-marijuana activist, opened the museum at 9 Bleecker Street to preserve all things Yippie and maintained it as a residence. Beal wasn't at the party because in 2012 he was convicted of transporting 150 pounds of pot in Nebraska and is currently serving a prison sentence. The museum is facing a legal battle with a lender who is attempting to foreclose on the property, and a court date is set for January.

But the legal troubles facing the Yippie Museum seemed miles away at Pieman's party. Paul DiRienzo, who has long been involved in the Yippie community and met Pieman in the mid-70s, fondly recalled their capers from the 70s and 80s. The Yippie Museum isn't as involved with social activism as it was back then, but there are still poetry readings and an open mic night every Wednesday. Occupy Wall Street protesters used the museum as a meeting space in 2011.

"Aron Kay, more than anyone I've ever met in my life, has taught me how to be an activist," said DiRienzo, who hosts a progressive talk show called "Let Them Talk" Tuesdays at 8 p.m. on Manhattan Neighborhood Channels. He said there wasn't a single appearance in New York City by Ronald Reagan that the Yippies didn't protest.

Pieman himself, who's confined to a wheel chair, recalled a particularly memorable anti-Reagan demonstration the Yippies held called the "Ballet for Bullets." They were protesting the Iran-Contra Affair and Reagan was the embodiment of the scandal. The president was attending his son's ballet performance at Lincoln Center, and the Yippies held a counter-ballet outside in the street.

"Picture myself, a pregnant woman named Ruth, and Dean Tuckerman - who had cerebral palsy - dancing around in tutus, dancing the Ballet for Bullets. We stole the show from them," said Pieman. "Whenever Ronnie boy would show up, we would have to be the pain in the ass."

Cake was served and speeches were made. Resistance songs were sung and guitars were strummed. Pieman's daughter, Rachel Kay, a vegan and animal rights activist, said it was good to see her father, who has health issues, so energetic.

In an interview later, DiRienzo said of the Yippie Museum, "It was like an intellectual salon. That's what would be the loss if they lost this place, it was a place where people from all over the world came at one time or another. Every amazing type of person, radical activists from any corner of the world you can imagine, passed through the [Yippie Museum] at one time or another."

From the guerilla-style Rock Against Racism in Central Park to organizing pro-marijuana marches, and of course hounding Reagan whenever he deigned to visit the Big Apple, the Yippies have been a consistent counter-cultural presence in the city.

DiRienzo recalled a device made by the Yippies' sound guy called the "sound cannon," which was two giant horns sitting atop a six-foot pole that was connected to an industrial strength cart. The rig could be dismantled into the cart and sealed up, making it impossible for the police ? short of using a blow torch ? to get into it.

"We could then go and make some hard-core sound," said DiRienzo. "The city was ours in those days."

As for the future, DiRienzo isn't sure what will happen, but he knows that the people who made the Yippie Museum what it is are still around and may have a few tricks up their collective sleeve.

"A lot of people say we should just rent another space," said DiRienzo. "But there's an emotional connection to this place that we put our blood, sweat and tears into. It can't be quantified."