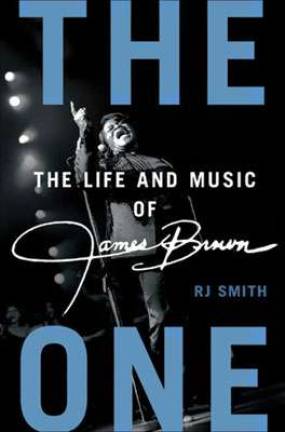

Radical Discipline: James Brown bio gets on The One

By John Lingan Of course James Brown's 1986 autobiography, The Godfather of Soul, begins outrageously: "I wasn't supposed to be alive?I was a stillborn kid." It's a contradiction and a medical impossibility, but no bother. When Brown died on Christmas Day 2006, aged 73, he'd played more than 80 shows in the preceding year, many of them in Europe. He'd been a PCP addict for over two decades and still performed acrobatically enough that he required post-show painkillers. In other words: Don't talk to James Brown about medical impossibilities. His whole life was one long affront to his potential limitations. The stillborn anecdote might seem like typical self-mythologizing bluster, but the biggest takeaway from R.J. Smith's new biography, The One (Gotham, 2012), is that Brown's weapons-grade ego was the product of profound emotional scars. Smith doesn't dwell on this fact, but it lurks behind his every page and quote. Brown was abandoned by his mother and abused by his dad and was dancing for strangers' money before he hit puberty. He literally knew how to hustle before he knew how to love. "Communicating basic emotional information to human beings was something [Brown] only learned later, after he found a way to make people care," Smith writes. "The one place he did get emotionally heard, and fed, was on stage." Offstage, the Star Time aura faded fast. Brown routinely exploited even his most devoted band members, most of whom eventually quit in anger. He had no meaningful artistic collaborations with other artists during his prime and barely ever co-wrote a song (though he often included others, including his own children, in the songwriting credits to ease his tax burden). In one confidant's telling, he was incapable of anything other than sexual relationships with women and he had no one, male or female, that he'd consider a friend. He was ceaselessly creative, but creativity was just another way of asserting himself and proving his domination over others. The key irony of Brown's life, and the thing that has made him such a rich muse for generations of writers, is that his very pathological selfishness made him an ideal civil rights idol. By merely following his natural, surely unhealthy need to be the alpha dog, he communicated that such a desire was even possible for a black American. His assertiveness was revelatory for a community in desperate need of self-respect. But he always reminded them who came first: When Brown taught his audience how to "do the James Brown" during his late-1960s performances of "There Was a Time," he showed black Americans how to be themselves by acting more like him. Brown's relationship and importance to the Civil Rights Movement is complex enough to warrant the kind of multivolume biography that Robert A. Caro and Taylor Branch have afforded other icons of the era. The One isn't nearly so ambitious, though Smith's research is often stunning and his critical treatment of Brown's music and performances is always insightful. He neglects to mention what year Brown was born and makes no significant mention of the man's nine kids, for example, but he situates Brown's career within a larger African-American cultural context stretching from the plantation field to Afrika Bambaataa. He also deserves credit for his book's title, which emphasizes the rhythmic structure of Brown's work over his many fawning nicknames. By laying heavily into the downbeat, Brown anchored his huge bands as they chopped the rest of the bar up into jagged, staccato syncopations. The one was his organizing principle, the fundamental ingredient to his visionary style that, in Smith's words, "created a new kind of space" in pop music. To read the full article at CityArts [click here](http://cityarts.info/2012/04/17/radical-discipline/).