street corners that gave women the vote

So revered are Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton that a statue of them will be erected in 2020 on the Literary Walk in the Central Park Mall to mark the centennial of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that gave women across the country the right to vote.

But far less attention has been paid to another pioneering women's rights organizer, Stanton's youngest daughter, inveterate Upper West Sider Harriot Stanton Blatch, who resided at 250 Riverside Drive off 97th Street — and lived through most of the 72-year struggle for suffrage.

Born just eight years after the first women's rights convention was held in Seneca Falls in 1848, Blatch followed the trail blazed by her mother — helping to marshal the great fight until New York women finally got the vote on Election Day in 1917, and suffrage at last went national in 1920.

Among her triumphs: In 1907, she founded the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women, which trained working-class women to campaign for suffrage and was “open to any woman who earns her own living, from a cook to a mining engineer. Then in 1910, she organized the city's first blockbuster suffrage parade, a march down Fifth Avenue climaxing in a giant rally in Union Square.

Blatch and thousands of like-minded activists transformed virtually every nook and cranny of Manhattan — its streets, salons, townhouses, tenements, clubhouses, concert halls, vaudeville houses, boarding houses, hotels, parks, pools, auditoriums, alleyways and office buildings — into a living, breathing operational base for the suffrage movement.

For roughly three-quarters of a century, they deployed the island's built and natural infrastructure to advance their cause. And now, for the first time ever, the geography of those places that make up the suffragist landmarks of New York have been painstakingly mapped by a team of researchers at the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission.

With little fanfare, no public events and only a press release issued on November 2, the LPC posted an interactive story map online — “NYC Landmarks and the Vote at 100” — that looks back at the attainment of women's suffrage, commemorating the centennial anniversary of the vote in New York through the lens of the city's landmarks.

The map documents dozens of LPC-designated landmarks and other historic sites to recount the tales of the places where suffragists lived, worked, huddled, organized, marched, rallied, campaigned, fundraised, demonstrated and created institutions that changed the face of the city and the nation, the agency says. It is accompanied by text, photos, maps and videos.

“These spaces — residential, institutional and commercial buildings — are the treasures of our city and a part of the shared heritage that binds us together,” said Meenakshi Srinivasan, chair of the landmarks agency. “They tell a story that's vitally important today as we continue to honor and further the legacy of the great suffragists.”

The site will enable visitors to honor the “magnificent women, and the He-for-She activists, who helped shape the suffrage movement” in New York, which was the “birthplace of the women's rights movement,” said First Lady Chirlane McCray in a statement.

Consider the case of Blatch, who was born in 1856 and died in 1940, a Vassar graduate with a degree in mathematics who was never quite as celebrated as her mother, but who was viewed as an extraordinary and inspirational force in the marathon battle for the franchise.

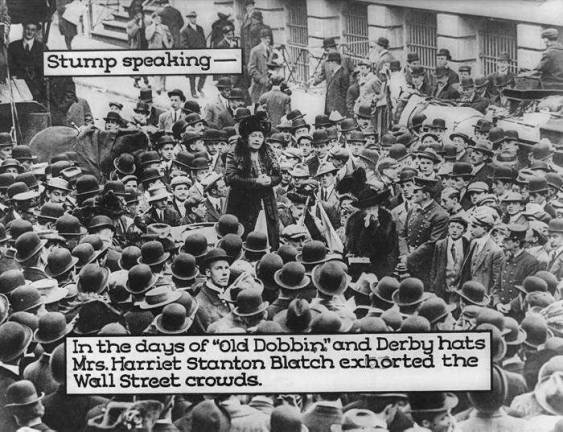

In effect, the Manhattan streetscape was her office: She would mount her soap box, literally, at the corner of Wall Street and Broad Street to exhort passers-by in the financial district to support a woman's right to vote. And she would rally her supporters beneath the towering bronze equestrian statue of George Washington in Union Square.

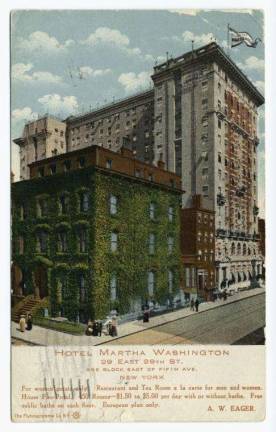

Blatch didn't only work the island's outdoor street corners. She gave rousing speeches at Cooper Union in 1907 and Carnegie Hall in 1909, the grand institutions that hosted hundreds of movement events, and she was a regular at the women-only Martha Washington Hotel, which served as headquarters for a council representing 18 separate suffrage societies.

For retreat, relaxation and retooling her speeches, there was always the Victoria Apartments, the nine-story, George Pelham-designed, 1902 Renaissance Revival building where she made her home.

“Most of the great and wondrous ideas of the suffrage movement were either New York-born or New York-borne creations,” said New York University journalism professor Brooke Kroeger, the author of “The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote.”

From strategic and tactical approaches, to pageantry and parades, from extravaganzas to regimental campaign operations, and even including one “fairly disastrous attempt at a vaudeville sketch” that was staged at the Hammerstein Ballroom on West 34th Street, Kroeger cites the flurry of Manhattan-based creativity that helped define the movement.

As for the so-called suffragents, pioneers of men's engagement with women's rights, Kroeger describes Max Eastman as a “charming, dashingly handsome new denizen of Greenwich Village,” who became secretary in 1909 of the Men's League for Woman Suffrage, founded in his apartment.

Now turn back to the LPC's “Vote at 100” to pinpoint the peregrinations of Eastman: The left-wing activist and radical socialist, who published then-subversive magazines like The Masses and The Liberator, first lived at 118 Waverly Place near Sixth Avenue, which served as the early headquarters of the Men's League, the interactive site says.

By 1917, he had moved to 6 East 8th Street, off Fifth Avenue, where he continued his agitation for women's rights, and in 1920, he decamped to 11 St. Luke's Place, off Seventh Avenue South. Eastman moved to the Soviet Union in 1922 — and returned to the Village two years later as a fierce anti-Communist who denounced the Soviet state until his death in 1969.

Another focus of an eight-person LPC research team — led by Srinivasan and Michael Caratzas, the agency's senior researcher — was the Polish-born Rose Schneiderman, 1882-1972, who worked in a Garment District cap factory and was one of the organizers of the United Cloth and Cap Makers' Union in 1904.

From her leadership of striking immigrant female garment workers, she moved into the top ranks of Blatch's Equality League of Self-Supporting Women and won fame as the movement's most spellbinding orator.

Schneiderman, who sometimes clashed with wealthier suffragists, lived with her family at 57-59 Second Avenue off East Third Street starting in 1905.

During a Cooper Union debate in 1912 between suffrage proponents and opponents, she famously took umbrage when a state senator said that voting would “rob women of their delicacy.”

Schneiderman's response: The working women of her acquaintance would not “lose any more of their beauty and charm by putting a ballot in a ballot box once a year than they are likely to lose standing in foundries or laundries all year round.”

It was also Schneiderman, a friend of Eleanor Roosevelt, who summed up what the woman's civil rights movement was all about in her 1912 speech to a gathering of moneyed suffragists, which is often quoted to this day and for which she is best remembered:

“What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist — the right to life, and the sun, and music, and art,” she exclaimed. “The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with.”

That moment finally arrived in New York on November 6, 2017.