Moves Like Morton

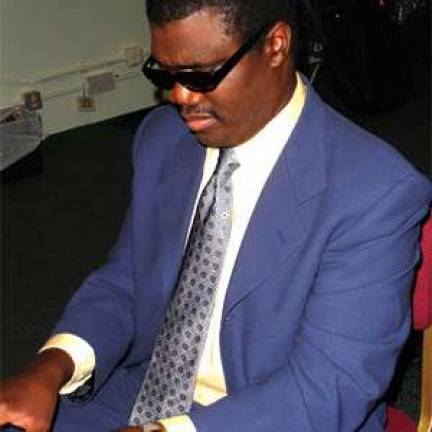

Marcus Roberts sets his own rules Jazz musicians pushing beyond the standard deviations advance the art form, and pianist Marcus Roberts stands out among many excellent current keyboard players with a thrust all his own. Performing the 1920s classics of Jelly Roll Morton faithfully yet also revised at Jazz at Lincoln Center May 11 and 12, and collaborating with banjoist Bela Fleck on record and at the Blue Note June 5 through 10, Roberts has been and will be neither strict neo-conservative nor outright populist, not representative of trends nor an outlying iconoclast. He's his own man, creating quite freely within explicit structures, exploring new associations while asserting uncompromised individuality. Roberts' music is odd, interesting, utterly unpredictable and fun to hear. In Western European classical music, one knows how the music goes and takes satisfaction in its realization. In jazz, we may know what the musicians start with, but thrill to follow their improvised paths forward, unsure of how and where they'll arrive. Jelly Roll Morton's compositions for his Red Hot Peppers are highly specific, recalled with precision by fans. Roberts, who is blind, took transcriptions of Morton's recordings and reharmonized them to get new, rich, coloristic blends from trumpet, trombone, two saxophones, clarinet, piano, bass and drums. That JALC-associated 'bone player Ron Westray, tenor saxist Stephen Riley and three young men who were Roberts' students at Florida State University had startlingly different soloing styles, stretching out in ways Morton couldn't have imagined but might well have applauded, didn't bug their leader at all. Indeed, on "Grandpa's Spells," "The Chant," "Deadman Blues," "Dr. Jazz," "Original Jelly Roll Blues," "Winin' Boy" and "The Pearls," Roberts strived to play nothing like Morton, coming up with strategies for each of his featured episodes that seemed capricious, if not random. Morton was no roughhouse blues and boogie guy; he filtered 19th-century European romanticism and bordello flourishes into syncopated stride and in ensembles was unfailingly supportive. Roberts, however, laid out right-hand-only single note lines with perverse restraint of momentum, threw down power chords and clusters in a frenzy, concentrated for a chorus on the bell-like highest notes of the piano and added contrasts and comments to his horn players' efforts. Westray blew like a burbling brook, Riley employed a strangely hollow, hoarse tone on anarchic, late-swing era fragments of phrases, and the kids Joe Goldberg (clarinet), Alphonso Horne (trumpet) and Ricardo Pascal (tenor and soprano saxes) walked the line between Hot Peppers fidelity and their personal impulses, usually sustaining the balance. The concert I heard, the first of two, was fascinating, though the band hadn't completely jelled. Drummer Jason Marsalis kept strict time, right on top of Roberts in duet on "King Porter Stomp"; he and bassist Rodney Jordan are Roberts' regular partners. Piano and banjo are rarely heard together, but Bela Fleck is a rare banjoist, and with Roberts' trio on Across the Imaginary Divide, the combination sounds natural. Roberts is stately at moments, folksy at others, delving into tango and blues. This may not be jazz, or it may be an unexpected expansion of the art. Who cares? It's fun to hear. Reach Howard Mandel at [jazzmandel@gmail.com](mailto:jazzmandel@gmail.com%20)