Memorial for a Math Mentor

"Maybe I was chosen for the approximately five basketballs that I confiscated from students during your four years at Stuyvesant," he said. "Or the 17 Frisbees I took away, or the 113 decks of playing cards, or the 257 cell phones I took away and brought to Ms. Damesek's office." All prime numbers, he said, with a fist pump. Mr. Geller loved prime numbers. There were cheers.

He paused. "No, I don't think so," his tone leveling, his audience now hushed.

Everyone knew why he'd been chosen. He had cancer. And though he had been responding well to recent treatments, the disease was taking over.

Geller died five months later, on November 1, 2011, at the age of 65. Many memorials followed his death: the miniature football placed by his grave (he was a Giants fan); a commemorative issue of The Stuyvesant Spectator; two scholarship funds; and a book by his brother, about his cancer battle.

Now, three years later, Stuyvesant High School is adding one more: a memorial to his math teaching, to be placed outside his old fourth-floor classroom this spring.

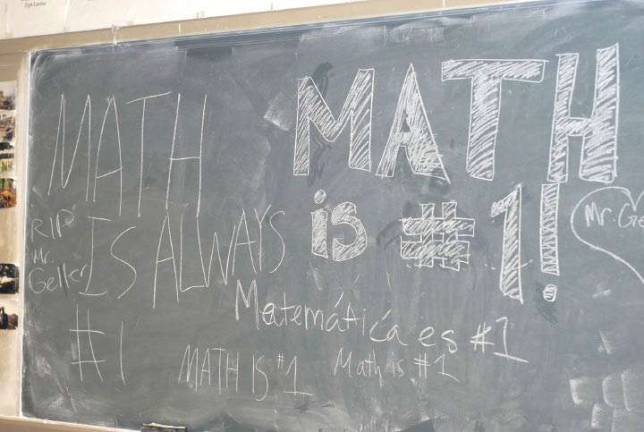

Geller's second wife, Barbara, donated her husband's library of math books ? a collection 400 volumes strong ? to the high school immediately after his death. She and her niece, Katie Kennedy, designed bookplates, which pictured Richard shouting, "MATH IS #1," the phrase he was known for repeating in class. Still, she thought, the school needed a real memorial.

With a few of his math department colleagues and the help of assistant principal Maryann Ferrara, Barbara started brainstorming more ways to commemorate her husband's life at the school. The idea of arranging the glass bricks by his classroom door to spell out his trademark phrase was discussed, but eventually the committee decided to install a plaque.

Black, with beige lettering, the plaque bears his name, date of birth, and date of death. "A master teacher," the text begins, "Richard shared his love and enthusiasm for mathematics and inspired admiration and respect from his students and colleagues." Lower down, the well-worn phrase appears in quotation marks: "MATH is #1."

But if math was #1, family wasn't ever far behind. He had other interests ? good food, cycling, travel ? but often they sprung out of love for his family.

When his daughter Liza went into remission for a childhood illness, his friends took him out to celebrate at Lutece, a top restaurant. That relief-filled night sparked a passion for well-prepared food and fine dining.

Every evening, he and his wife took turns making gourmet meals, savoring the one uninterrupted hour a day they had to spend time with each other. He often visited top restaurants and knew chefs by name.

When his son, Jason, became interested in cycling, he picked up the hobby too, and rode for miles. He gave guests the "five borough bike tour," rode to school from his home on the Upper West Side, and signed up for long bike trips with his wife.

It came first in 2001, in the nonthreatening form of a stage 1 melanoma. He had it promptly removed. But nine years later, his dermatologist found a suspicious mole that turned out to be a slightly more advanced melanoma.

Again he had surgery, and the procedure went well. His surgical oncologist reassured him that the cancer had not spread.

But by March, 2011, a persistent dry cough led Geller to the doctor's office for more tests. After a chest x-ray, they discovered that the cancer had metastasized and was now in his lungs.

"He never smoked a day in his life," his brother Harold insists. But Richard's lungs were covered in tumors.

The family Googled furiously. How long might he live? What treatment options were available? What were the latest drugs being tested and could he participate in the trials? They found some hope in the form of new research, but the more they read, the worse things seemed.

"I felt like shit, of course," Harold said. "For a malignant melanoma which has metastasized... the odds are very bad. I think only 15 percent live more than a year."

The cancer symptoms accumulated. There was the joint pain, the cold sores, the rashes, the fatigue, and on some days, difficulty sleeping and breathing.

"Even through all of this," Geller said, during the commencement speech, "the best part of the day is teaching math." His doctors tried to schedule appointments for after 3 p.m., so that Richard would miss as little school as possible. He graded papers in the hospital, and hours before he died, his son Jason heard him leading a lesson in his sleep. Geller was restless in bed, and then got up and said, "Take one, and pass the rest back. Are there any questions?" Those were his last words.

Though Geller had always loved math, he had not always dreamed of becoming a teacher. The profession had been a way of avoiding Vietnam, a war he deeply opposed. Signing up to teach at an inner-city school guaranteed that his name would be struck from the draft, so in 1968 he signed up to teach math at Junior High School 143.

He started teaching at Stuyvesant in 1982, where he also taught math and soon took over the math team. He covered the walls of his classroom with posters of mathematicians and newspaper clippings about the math teams' many victories.

One of his former students, Mike Develin, praised Geller for keeping the "200 rambunctious nerds" who made up the math team organized. "The juggernaut would not have existed without his keeping us in line and inspiring us," Develin wrote, on a memorial Facebook page of The Stuyvesant Spectator.

"And it's no small stretch to say that he was a pivotal figure in my becoming a mathematician," Develin added.

Geller won awards for his teaching, though his toughness didn't always endear him to students. The author of a 2007 book about Stuyvesant referred to him as "a grizzled math teacher" and "a notoriously tough grader."

"He was tough on them, but they learned a lot," Harold said. Over the years he'd had the opportunity to meet many of Richard's students.

Though Richard had many friends, his brother explained, he wasn't a socializer.

"He was shy and introverted, and that's something that the students probably wouldn't believe," Harold said.

The new memorials are important to Barbara, as she wants him to always be remembered for what he cared passionately about: teaching and math.

Both Barbara and Harold plan to visit the memorial within the next month, having seen the proofs but not the plaque in person.

Many of the students who remember Mr. Geller already paid their respects and contributed to their own memorials three years ago. They attended the funeral at Riverside Memorial Church, read obituaries, submitted stories to the student newspaper, wrote blog posts, taped pieces of paper that read, "MATH is #1" to their lockers.

But soon the school will have one permanent place of remembrance ? a reminder that life can be fleeting, death quick. As plain but as precious as prime numbers.