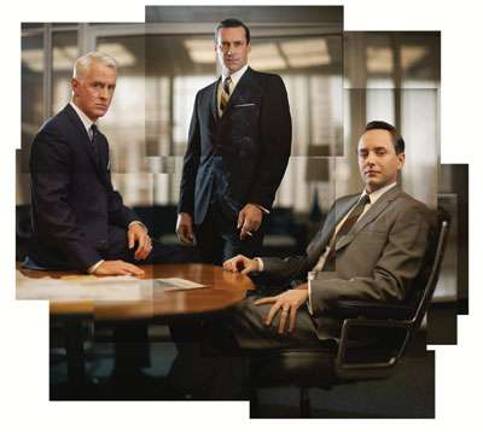

Mad Mania

"Smart" TV and the Gray Flannel Ego By Ben Kessler Mad Men, like The Sopranos and The Wire before it, now enjoys a singular cultural status. Neither pop nor art, it is smart TV. And smart TV, we're told, is not for analysis or even entertainment; it is to be dutifully let into our lives, much as we're meant to bring in the newspaper every morning. Smart TV is a unique kind of aesthetic nonentity, but even nonentities have to come from somewhere. Mad Men's creator Matthew Weiner, like HBO's three Davids (Chase, Simon and Milch, of The Sopranos, The Wire and Deadwood respectively), has a media profile that mixes elements of many leadership archetypes-he's part film director, part producer, part CEO. Because they preside over a vast creative apparatus rather than yoking themselves to any particular aspect of production, Weiner and his fellow smart showrunners are presumed by journalists to be above the unfortunate susceptibilities that plague the individual artist. As part of this post-auteur framework, the protagonists of smart TV shows are usually distorted extensions of their creators. Mad Men's Don Draper is given to pronouncements that have no precedent in the early-1960s mainstream but could easily fit into contemporary liberal-bourgeois conversation (e.g., "You're born alone and you die alone and this world just drops a bunch of rules on top of you to make you forget those facts, but I never forget. I'm living like there's no tomorrow, because there isn't one."). In Draper/Weiner's case, Mad Men's benighted '60s perspective lends a transgressive thrill to this sort of sentiment. For certain viewers, there's perfect perversity in a character embodying chauvinism and capitalism who carries on about the meaninglessness of existence like a dweeb from a recent Woody Allen film. Someone of a New York magazine mindset might ask with fascination, "How'd a guy like that come by such deep thoughts?" Set in 1966, Mad Men's fifth season starts with a civil rights protest on a Manhattan sidewalk. Right away, Weiner proffers a scene designed to answer media folks' demands for a deeper engagement with race on the show. But Mad Men's makers show their true colors by ending the teensy protest prologue on a note of pseudo-liberal self-congratulation. After being waterbombed by ad men (not our heroes) from the offices above, a black protester gets the last word, a tin-eared summation that deadens the civil rights dialectic: "And they call us savages." To read the full article at City Arts click here.