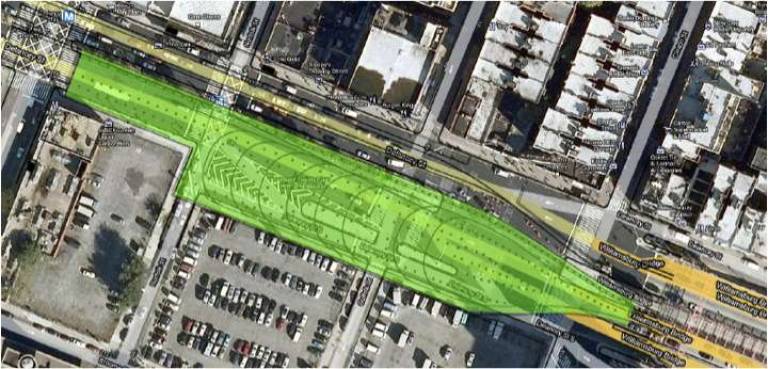

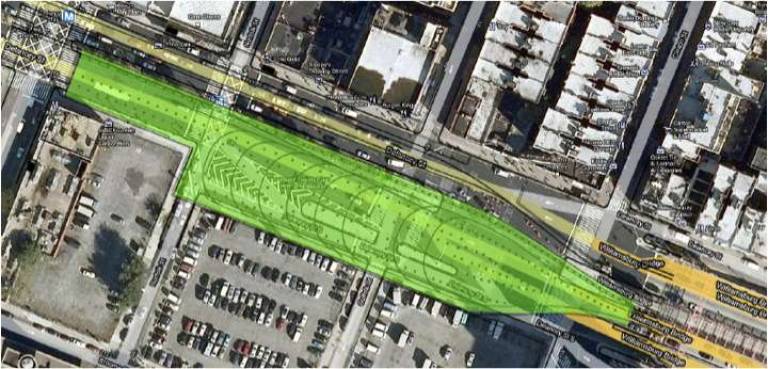

The plan to construct a massive public space underground has raised significant capital and support As Lower East Side residents continue to clamor for green space, one project on the horizon ? or rather, under it ? inches closer to the reality of bringing a brand new natural haven for the local population. The LowLine, as the project has come to be called following the popularity of its distant cousin the High Line, is still just an idea. Still, it's garnered widespread and official support over the past year, earning the accolades of every elected official who represents the turf it potentially sits under as well as the enthusiastic backing of residents of the Lower East Side and all over Manhattan. The project, originally called the Delancey Underground for its location underneath Delancey Street, was envisioned by James Ramsey, a designer and inventor, and Dan Barasch, who has previously worked for Google, PopTech and New York City government. Ramsey's design practice RAAD has built projects across the city and country, but the conception for an underground park is, well, groundbreaking. The space that Ramsey and Barasch hope to transform is a 60,000 square foot empty cavern that was built in 1903 as a trolley terminal, housing the streetcars that traveled over the Williamsburg Bridge. The long-abandoned site is still owned by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) but has been sitting empty and forgotten since 1948. [caption id="attachment_66442" align="alignleft" width="300"](http://nypress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Rendering.jpg) A rendering of what the LowLine, a proposed underground park on the Lower East Side, could look like.[/caption] Last week, a coalition of elected officials signed a letter urging the city's Economic Development Corporation to seriously engage with the MTA in negotiating the transfer of the underground space over to the city in order to get the ball rolling on the park. Signers, including both New York senators, members of Congress, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, State Senator Dan Squadron and Council Members Rosie Mendez and Margaret Chin, cited a study by HR&A Advisors and Arup, which showed that "the LowLine could generate at least $15-$30 million in economic benefit to the city by way of increased sales, hotel and real estate taxes and incremental land value, and would create 560 full time equivalent jobs during construction." They also lauded the project's potential to bolster local businesses during the day by attracting tourists and residents to the area when the sun shines ? a problem that plagues the nightlife-centric neighborhood. Barasch called the support from local leaders "an important milestone" for the project. "We've spent a ton of time talking with the MTA about the site, we've commissioned a formal feasibility study to assess the site, we have an estimated cost [$60 million] that is certified by an engineering team, we've built up an organization," he said. "I think the MTA is now ready to sit down with the city and ask the basic legal questions of how it can be transferred. The MTA is not in the business of building public parks, but the city is." [caption id="attachment_66443" align="alignright" width="300"](http://nypress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Preview.jpg) A preview installation of what the LowLine could look like when it's completed.[/caption] If the city successfully negotiates the transfer for the site, the next step will be to issue a call for proposals from design and engineering teams to create something there. Barasch and Ramsey aren't officially locked in until the city accepts their proposal, but as the team that spearheaded the project and has invested hundreds of thousands of dollars and invaluable creative energy into it, they hope they'll have an edge in the competitive process. For now, Barasch says that they're focusing on securing capital from a variety of sources ? public, private, institutional, individual ? and on continuing to engage the community to find out what kind of space they want. While the most intriguing aspects of the LowLine have to do with its logistics ? it will use solar power to filter in natural sunlight and grow plants underground, for example ? the most important element is that it will serve as a community space, Barasch said. "We want to be a new organization that doesn't force design and concepts onto the public but really brings people into the process itself," he said. They've recently worked with a group of local high school kids, teaching them about public space and its purposes and uses, and then challenging them to come up with their own design ideas for the LowLine. Their ideas range from "really impossible, like flying dogs, to the possibility of mechanical robotic animals in the space," said Barasch. Last year, the LowLine concept was a new and perhaps crazy idea to most people; now, it's seeming more and more feasible. Barasch hopes that by next year, he and his partners will have been given the green light to start preliminary construction on what he calls "a cultivated underground garden which will certainly change people's perspective on what's possible."