LIVING THROUGH 9/11

The day everything changed Nearly a decade after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the New Yorkers who watched the planes hit the Twin Towers carry those images with them to this day. To commemorate the anniversary of this tragedy, Tribeca-based writer Wickham Boyle presents a powerful, visceral account of the day through the stories of five disparate eyewitnesses. -All accounts as told to Wickham Boyle

Father Raymond Nobiletti Pastor, Church of the Transfiguration It was that beautiful, clear day. I said the early mass at the Church of the Transfiguration on 29 Mott Street, then I went and voted. When I was back, the office said a plane hit the World Trade Center. We at first thought it was an accident. Then we got the call saying, "We need a priest down here." I started to gather my stole and my oils, and just then, a plane hit the second tower. The screaming and yelling from people in the neighborhood buildings was terrible. We realized it was an attack, not an accident.

I ran between the courts and there were literally thousands of people coming out of the buildings, flooding the streets, screaming. I was bumping shoulders, being jostled at every turn. I thought, "Why am I doing this when everyone is running the other direction?" I went to the front of the Millennium Hotel, where they'd set up a triage center. People came and hugged me and fell into my arms. Maybe they weren't even Catholic-or Christian-it was the symbolism, I suppose, they felt from me.

Many were panting, burned and asking me to call people. One woman was totally burned, her face was exposed, I recall praying the "Our Father" with her. I was there for an hour when we heard the crack of the South Tower collapsing. The top 20 floors came toward me. I ran to the gate of St Paul's churchyard and grabbed on the gate, and then people grabbed onto my legs. In an instant, we were covered in the ash and paper and it was totally dark for what felt like a very long time. The ambulance near us was crushed. A policeman was screaming, "Get out of here, the next one is gonna come down."

I didn't realize that I was covered in ash and bleeding. I walked down Fulton Street, trying to get back to the church, and then the North Tower collapsed and the impact pushed me into the street. I continued to walk to Chinatown-as I went past the courthouse, some parishioners recognized me and tried to wash me off, but everything was stuck. I got to the church. I went to change my clothes and I found several patches of burnt flesh. I changed and came down. We knew that 19 people, new immigrants from our church, were missing. We later found that they were taken to New Jersey on a ferry.

We had funerals for Cantor Fitzgerald workers and firefighter funerals, and still it seems as if many of us have not recovered. It was a time that really changed Chinatown. For the anniversary, I think about the spirit of helping from the staff of the hotel with towels, of the police moving us out of the way and of the court workers offering water. All of the small things that came together as a community. It gave me an appreciation of how sacred the site became from the people. It is the presence of God's grace in the face of evil. Henry Sherwin Wickham Boyle's Son and Downtown Paralegal I'd turned 13 a week earlier and I'd joked that Sept. 11 was the second first day of school because my mother had been mistaken and made us go to school on that Monday. We had to go back home and return the next day, Tuesday, Sept. 11. So it had a very jokey feeling to the start of the day.

I was in Spanish class in the part of I.S. 89 that faces the West Side Highway. We felt the building shaking first. We watched the planes fly pretty close to our eye level. It was close enough to see the windows in the plane. Then we saw it hit the building. The school made an announcement that there had been a gas explosion and all the kids were evacuated to the lunchroom. We were all milling around, still being kids, still joking; we didn't see the second one hit, but we felt it. Then you [Boyle] came and took me and a bunch of my friends out.

We were all on the West Side Highway when the first tower was collapsing. I never broke down and cried, but a lot of kids were losing it. I just wasn't sure why it didn't shake me like the other people. Afterward, my instinct was to find ways to be helpful.

After we got home on the first night, it was quiet and supplies were being delivered. I went out and loaded and unloaded boxes onto a neighbor's uncovered loading dock. The second night, it started raining and all the supplies were out in the rain, I heard it from my room and I got up at 3 or 4 in the morning. A neighbor kid named Eric, an older kid, was there and we moved all of the supplies. There was water pouring on all the food and clothes. We moved them undercover. It felt good to have a real task that might be a help.

The first night, I went out with my dad and when we stepped out it was the moment when World Trade 7 or 5 fell. People started running again.

I.S. 89 was closed and they sent us to the Lab School on 17th Street. It was hard to get back Downtown past Canal Street, as they had frozen the zone where I lived. But once you were down here in the frozen zone, there wasn't any real regulation at first. I remember talking to the firefighters, asking if they'd found anybody and the guy responded, "We're not gonna find any people alive." I was 13 years old and it was intense to think they wouldn't find anyone else alive. William Nevins Private Investment Advisor and Art Dealer I worked at Lehman [Brothers] for 20 years-I was a bond salesman. We were right across the street from the towers. I saw everything. It was on a Tuesday morning, a clear day. I was at the post, surrounded by computer screens and a big TV above everything so we could constantly watch the news. The TV abruptly switched and the picture was no longer news, but what looked like some Hollywood blockbuster film where aliens have put a hole in the World Trade Center. I swiveled around and said, "Who changed the channel?" Then I looked out the window and I saw a whiteout, tons of paper flying by the windows.

Our first thought was pilot error or a small Cessna. I knew that if it was a small plane it would bounce, like an insect off a windshield.

There were lots of phone calls saying there were people falling out of the windows. We all turned and looked. There were people holding hands or jumping one at a time, three at a time-holding hands. We were shocked. Most of our floor did not evacuate until the second plane hit. From out of the corner of my eye I saw a plane heading north, and when it hit the tower my knees buckled. I hit the ground. I went and got my keys and wallet and walked down 29 flights to ground level and over to the marina in the World Financial Center.

It was chaos. Everyone was running toward the boats to get out of there. I walked through to Tribeca, on over the bridge. The North Tower had dropped and collapsed in front of your eyes. I said, "Game over-the world has now changed." I walked to my apartment on Fifth Avenue near Washington Square Park. All the phones were jammed, but within 25 minutes, there were people who knew where I lived and they just kept arriving.

We turned on the TVs and watched in disbelief. Within minutes, there were two or three F16s constantly circling Manhattan. They shut down the flights and we heard the newscasters say, "This was an act of war. We are at war." From then on, we sat in disbelief, watching the chaos on the street going from downtown to uptown. Everything changed.

Empty Socket

My eyes search the horizon from my Tribeca home; they roam over the landscape idly like an errant tongue groping the empty socket that earlier held a gleaming tooth. Over and over, my gaze comes to rest on the spot where the twin towers of the World Trade Center held sway as mighty landmarks. "Go south toward the towers," I would direct endless foreign visitors.

Now in the darkness of the third night there is a crescent moon and stars, unusual in downtown Manhattan. But after all, these have been three glorious Indian summer days with crystal-clear skies, shockingly filled with acrid smoke and choking particles.

-Excerpted from Wickham Boyle's book, A Mother's Essays from Ground Zero Abby McGrath Filmmaker and Director of Renaissance House, an Artists' Retreat Tony [McGrath's husband] and I were driving down the West Side Highway to see our film editor with all of the equipment and the raw footage in the car. We saw something hit the rear of the car ahead of us. At a light, I got out to tell the guy in front what had happened. I looked up, and something had gone through the sunroof of our car, too. Then we noticed reams and shards of paper flying out of the World Trade Center. There was a group of kids going into Stuyvesant High School who turned and were pointing. It was ominous, like a horror film. Lots of quiet and pointing. When we looked up, there was a hole in the World Trade Center.

We assumed there was some kind of gas explosion. There was no sense of urgency. I left Tony with the car and told him I was going to buy a quick cheap camera for insurance purposes. While I was looking, I overheard people talking about a war because someone had flown a plane into the WTC. When I returned back to the car, there was the loudest sound I'd ever heard. Tony dove under the car, but, you know, I have a big backside and I couldn't slide all the way under-my legs were hanging out and I thought I would be run over. Another man dove under our car and he said, "Stay here, there's more of them out here."

When it was quiet, we clambered out and saw that our dog Louise was gone. She had jumped out of the open car window. The noise was so loud and close when the second plane hit that the noise stayed in my head and I felt it in my bones.

Now my only aim was to find Louise. I went to the dog run and it all still seemed normal. Children were still playing and there were no sirens yet. I headed back to the car. My husband was driving away because someone told him he had to go. I raced up to him at a stop sign.

We drove to Battery Park. A female cop said to get out of the vehicle. We left the car and went into the park. It was packed; everyone was told to go into the park and I was being mashed like at a rock concert. Some people were in a restaurant-the doors were locked and people were banging on the glass doors to be let in, but no one would open the doors. So many people were screaming and crying.

I followed the waterline, but you couldn't see well because of the haze and paper falling everywhere. I was afraid I might fall into the river, but we kept trudging north. At some point, we could see the second tower falling. It seemed as if it was in slow motion. One floor, kerplunk, then another. I knew our editor lived on Pearl Street and I thought we could make it there. We walked there not knowing that we had ash all over us.

We had no idea what happened to Louise. We later learned that she jumped out with her leash on and started running. A man we now call The Captain-he is the captain of a ferry that goes to the Vineyard-saw her and grabbed her, thinking her owner would come. The Captain ran to the water and there was a boat tethered there. He jumped on and threw Louise on the boat. The Captain and the owner of the boat decided that they would ferry people over to New Jersey. All day, they took runs back and forth across the Hudson River with Louise as the co-pilot, comforting children and scared adults alike. Impressions with Nick Griffin

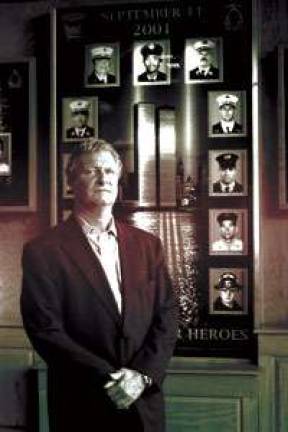

Daniel Bergstein, a 1980 alum of Stuyvesant High School, died on Sept. 11, 2001, while at the Port Authority office in Tower One (he served as board secretary for the organization). Nick Griffin is one of the co-founders of the Daniel Bergstein/SHS '80 Memorial Scholarship, which gives an annual cash award to an outgoing Stuyvesant student on their way to Columbia University or Barnard College. Griffin sat down to reveal how the fund serves as a memorial not only to Bergstein but to the friendships he formed while at Stuyvesant.

How did you know Dan [Bergstein]?

We both grew up on the Upper East Side and went to the same public junior high in 1972. We ended up at Stuyvesant together. But after high school, the next time I saw him was at our 20th reunion in 2000. There were probably 200 members of our class there. Unfortunately, it was one of those situations where someone taps you on the shoulder, you say, "Hi," and then there is someone else to say hi to. The next time I thought about Dan was when I found out his name was on the list of the missing.

He was a very thoughtful and dependable guy. He was in the towers in the first bombing in the 1990s and was one of the cool heads who helped people get out.

Dan was born and raised in the city. He attended Columbia University and worked for the Port Authority. Why do you think Dan spent most of his life in New York City?

I think New Yorkers are New Yorkers for a good reason. Dan, as you said, did all of his education in New York City, including grad school, when he went to CUNY [The City University of New York]. I think he was a believer in public education and that is why we put together a scholarship. It was really to honor his commitment to public education. As a city boy, it made sense for him to chart that sort of course and?work in the public sector.

How did the idea for the fund come about?

I ran into a bunch of old classmates at St. Paul's Church [at Bergstein's memorial service]. We said that we needed to do something. We didn't want to do some one-off event. The fund was something we could do on a sustained basis. We wanted to do something to carry on the memory of not only Dan but of our friendship with him. This is something that will remind people of the lasting ties of friendship and comraderie.

How much has the fund given so far? What's the ultimate goal?

We have given over $15,000 in total since 2003. Essentially it is a cash reward and is the largest award given by a Stuyvesant class to a student that is done on annual basis. We have collected a lot more money that that. The proceeds from the endowment have gone towards these annual awards.

We set an original goal to raise $100,000 [for the endowment] and the basis of our thinking was with $100,000, the endowment would be able to generate up to about $5,000 a year in annual scholarships. We have a low-key approach to fundraising and so far we have been successful. I think the success of this effort says a lot about a unique bond between people who grew up together in five boroughs, who knew each other, were friends or acquaintances back when we were young. I think those bonds are really important.

A portion of the revenue from this issue of Our Town Downtown will be donated to the Daniel Bergstein/SHS '80 Memorial Scholarship Fund as well as to the 9/11 Memorial Fund. [Ed. note: Manhattan Media President and CEO Tom Allon was a former classmate of Bergstein's at Stuyvesant High School.] Liz Thompson Director of ArtfulAction Consulting and Former Executive Director of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Whose Offices were in Tower Five I want to tell the story backward. I was actually thinking of giving myself a birthday party this year on Sept. 11, even though my actual birthday is in the spring, because this is the first time I feel completely free of 9/11 stuff.

It has taken a long time to feel free. I didn't want it to be a memorial of how scary or unsettling it was. All of that made me shut down. It is sort of a triumph of now being really clear, honest and fearless about examining who I was [then].

Even though-on one hand, the years after 9/11, after I stopped working so intensely for LMCC, felt like wasted years. Nothing interested me. I felt as if I had sawdust in my mouth. I didn't cry for six or seven months. My kids kept saying, "Don't you think you should see somebody?" I kept saying, "I'm all right." I got my staff to see people for therapy, but I eschewed it.

LMCC didn't lose any staff, but we lost a Jamaican artist-in-residence, Michael Richards, who was working on a piece about the Tuskegee Airmen, the black fliers.

I learned later that I took the last elevator down because I was meeting with Geoff Wharton, who was Silverstein's COO. We were talking about LMCC's future at a breakfast at Windows on the World; we had pro bono offices in Tower Five. Geoff had to find somebody before the workday began, and he apologized for cutting the breakfast short. I got up to leave with him. The express elevator was broken and the other elevator to the sky lobby opened. We got in. Then we took the next elevator to the lobby. If any of the two elevators hadn't been in sync, it would have been a different story.

As we walked out of the elevator into the lobby, the first plane hit. We heard the glass. It was like a vacuum. It was as if the air got sucked out of the lobby. We heard the crashing and Geoff took us down to the sub-basement, looking for a command center. Down there, a man came running toward me with smoke pluming off of him. I turned and saw an exit sign and I got out by the Winter Garden. The first thing I saw was a pregnant guard and I walked her across and out back. We were all milling around outside and then I saw the second plane hit. I could only think about the people in the plane. Then I started to walk away from the site. I encountered someone I knew from the Berkshires. He took me home to his loft.

After 9/11, the spirit of Downtown was fantastic; it was like a small town. Everyone was caring and concerned. There was a sense that we wanted to rebuild and rebuild right. You still couldn't breath. We had three temporary offices before we landed on Hudson Street. We didn't miss a beat, not one grant deadline, not one community board meeting. The staff was amazing. Afterward, there was nothing else to do but work intensely and build and take advantage of the community feeling.